Homeownership is the primary way most Americans build wealth. And for most people, buying a home doesn’t happen without a mortgage loan. Altogether, home loans amount to billions of dollars flowing into Boston every year. But this infusion of money doesn’t reach all parts of the city equally.

A WBUR analysis finds lenders make a significant majority of home loans in predominantly white areas in Boston. In a city as segregated as Boston, looking at the geography of where mortgage lending is happening — or not — reveals which neighborhoods continue to lose out on investments that others see.

“Unfortunately, it follows a pattern that we have seen in the past where certain neighborhoods in Boston, in a sense, get a much bigger piece of the pie,” said James Jennings, a professor emeritus at Tufts University and an expert on race, urban planning and economic development.

WBUR analyzed loan data for home purchases in Boston from 2015 through 2020. That’s 37,465 loans, totaling $24.1 billion. Here’s a snapshot of what we found:

- About 63% of home loans went to majority-white census tracts in Boston, while about 11% went to majority-Black census tracts.

- South Boston received more home loans than all of the city’s majority-Black census tracts combined.

- In most neighborhoods where people of color are the majority, white homebuyers still received the largest share of mortgage loans.

- Some lenders issued more than 20 times more loans for properties in white areas compared to Black areas.

Buying a home can create financial security, ensure housing stability and leave wealth for future generations — which can have an impact on a family and on a community. And economic development experts say home lending can influence how neighborhoods are shaped and transformed.

More Home Loans Go To White Areas

Many factors contribute to differences in mortgage lending, including turnover in the housing market, construction of new housing, property values and long-standing economic disparities. But the data reveals how access to homeownership is not equal throughout Boston.

“These disparities in lending continue to drive racial disparities in wealth, and racial disparities in wealth drive disparities in so many other dimensions of life: health, education, employment opportunities, well-being, etc.,” said Justin Steil, an associate professor of law and urban planning at MIT, who studies racial equity in housing.

The areas in Boston with a lot of mortgage lending have also experienced tremendous development, including high-end housing, in recent years.

WBUR’s analysis found significantly more new housing units were added in majority-white areas than other parts of the city. City data shows two-thirds of certificates of occupancy for new units were issued in majority-white areas, which account for less than half of the city. Fewer than 5% were issued in majority-Black areas, which constitute 17% of the city. About 25% of census tracts in Boston have no clear racial or ethnic majority.

South Boston Had More Loans Than All Black Areas Combined

Along Broadway Street, which cuts through the center of South Boston, there are juice bars, trendy restaurants and niche retail shops to pamper pets, plants and people. There are also construction sites and shiny new buildings.

In front of one building, a sign reads, “New luxury condos. Now accepting reservations,” in art deco-style font. Down the street, two other luxury condo developments promise even more high-priced dwellings, retail space and other amenities.

“There’s a certain kind of almost boutique atmosphere to it,” Jennings said during a walk through the neighborhood.

Strikingly, South Boston, which is 77% white, received more home loans — 4,689 — than all of the city’s majority-Black census tracts combined.

Jennings would like to see the same kind of injection of money and new development South Boston has received in other neighborhoods, where most people of color live. He said this would give those residents more opportunities to enjoy the benefits of homeownership.

“Owning a home — and having access to resources to own that home and also to fix it up — means that people have equity to start businesses. People have equity to pay for education costs of their children,” Jennings said. “People have equity to transfer wealth from one generation to the next generation.”

Mortgage lending can also help bring other types of lending into a neighborhood, according to Brett Theodos, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute who studies how capital moves in cities across the country.

“Home lending is associated with other lending to a very high degree,” Theodos said, such as for small businesses and commercial developments like grocery stores.

Even In Black And Brown Communities, More Loans Go To White Residents

In Boston, homes are expensive and in short supply. The highly competitive market makes it even more challenging for historically disadvantaged groups to buy homes. For some Black residents, that has meant leaving the city to make their dream of owning a home come true.

“I literally had no choice financially,” said former Boston resident Sabrina Xavier.

Xavier, 30, ended up buying a single-family house in Brockton last summer. She said she’s happy to have her own home, but there are downsides. It’s less walkable, and there are fewer food options and other amenities than where she has lived in Brighton, Dorchester and Roxbury. Xavier now has to commute over an hour by car and train to get to her public health job in Boston.

She purchased her home with help from the state’s ONE Mortgage, which offers a low down payment and other benefits for low- and moderate-income homebuyers. But Xavier said the amount she was pre-approved for just wasn’t enough to compete in Boston’s housing market.

“It felt horrible that I grew up in the city that I couldn’t even afford to live in,” said Xavier.

As the youngest of eight, Xavier always wanted to have her own property. That way she could build equity that might help her and future generations of her family.

“Hopefully things change in Boston where, you know, we’re not being pushed out,” Xavier said. “I feel like Black and brown folks are being pushed out of Boston because it’s so expensive, and they’re going to other suburbs where there’s less resources because that’s all they could afford.”

In fact, according to the 2020 census, Boston’s Black population has dropped compared to 2010. Hyde Park, Mattapan, Roxbury and Dorchester — where 75% of Boston’s Black population lives — each saw declines in the percent of Black residents.

The data WBUR analyzed showed that in most of these neighborhoods, white borrowers received the largest share of home loans. More than half of the loans approved in Dorchester went to white borrowers, even though white people made up about 22% of the population.

Amid these trends, some Black homebuyers are concerned about gentrification. Like Jha D. Amazi, who is determined to find a multifamily house in Dorchester, Roxbury, Mattapan or Hyde Park.

“I’m from here, and I’ve always been committed to pouring back into the place that helped raise me,” Amazi said.

The 36-year-old and her wife spend their evenings on various real estate apps and have looked at dozens of houses. The process has been a mix of excitement and frustration that has constantly ended with her getting outbid. Amazi said she’s considering leaving the state altogether if things don’t pan out in Boston.

“We’ll have to figure out how much longer we have in us before we throw in the towel,” Amazi said. “And if we have to look outside of Boston, then that’s a bridge we’ll cross when we get there. But, it is kind of Boston or bust.”

Some Banks Had Even Greater Disparities In Lending

Citywide, when looking at loans given to majority-white and majority-Black areas, white areas received nearly five times more loans than Black areas.

A closer look at specific financial institutions shows some with an even wider disparity. For example, large national lenders like JP Morgan Chase and Wells Fargo, as well as regional banks like People’s United and Webster Bank, made more than 20 times more loans in white-majority areas compared to Black-majority parts of Boston.

When asked for comment on WBUR’s analysis, many lenders pointed out that they fund various programs to help first-time homebuyers, increase accessibility to mortgage loans and create affordable housing.

“Massachusetts banks are working to ensure that all qualified homebuyers have access to fair and affordable mortgage products,” Massachusetts Bankers Association CEO Kathleen Murphy said in a statement. “Our members continue to innovate, creating programs and partnering with non-profit organizations and local governments to make the homeownership dream a reality.”

Connecticut-based People’s United made 27 times more loans in majority-white areas than majority-Black areas – the largest disparity of any bank.

The bank said it regularly conducts its own lending analysis and has found “no significant statistical difference” between its lending and its peers’ lending to Black residents in Boston from 2018-2020.

“Our underwriting requirements are applied equally to all mortgage applicants regardless of race, ethnicity, location, or any other prohibited basis, and applicants must meet the Bank’s underwriting requirements which include factors such as income, credit scores and debt-to-income ratios,” People’s United spokesman Steven Bodakowski said in a statement.

JP Morgan Chase made 25 times more loans in majority-white areas than majority-Black areas. The bank said that in 2020, it made a $30 billion commitment to improving racial equity and is expanding its presence in the city, including a new branch now in Mattapan.

It did not open its first Boston location until late 2018, although federal data shows the bank did make loans in the city before that time.

“We expect to serve more Bostonians with their home buying needs in the months and years ahead,” a spokeswoman said in a statement.

Housing advocate Symone Crawford, executive director of the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance, said more financial institutions should offer products like the state’s ONE Mortgage program, “so people of color can actually be able to purchase” homes.

Some lenders in WBUR’s analysis, including People’s United and Webster Bank, do offer that mortgage product, but many do not. Experts said that’s at least one of many potential solutions lenders could put their resources toward.

“We have the capacity to help Black and brown people into the housing market,” Crawford said. “And these lenders need to seriously put their money where their mouth is.”

Methodology And Other Notes

WBUR analyzed Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data for Boston. Under HMDA, financial institutions are required to compile and publicly report home loan data.

The data, which is reported to the federal government, includes various types of housing such as single-family homes, multi-family homes, apartment buildings and condos. Only home purchase loans were included in the analysis. Refinance loans were excluded. The loans were issued by traditional banks and other types of lenders, such as credit unions and mortgage companies.

WBUR looked at data from 2015 through 2020. The HMDA data is broken down by census tract. The population totals and demographic information for each census tract come from the American Community Survey (2015-2019). The majority race for any census tract is the group that makes up more than 50% of the tract. The neighborhood-level demographics came from the Boston Planning & Development Agency.

WBUR’s analysis did not focus largely on majority-Hispanic census tracts and majority-Asian census tracts because they represent a small fraction of census tracts.

WBUR’s story was inspired by WBEZ’s reporting on mortgage lending in Chicago.

The video atop the post is of properties on a street in Roxbury. It was filmed and edited by Robin Lubbock.

More Stories

House Loan Prepayment Tips to Reduce Interest

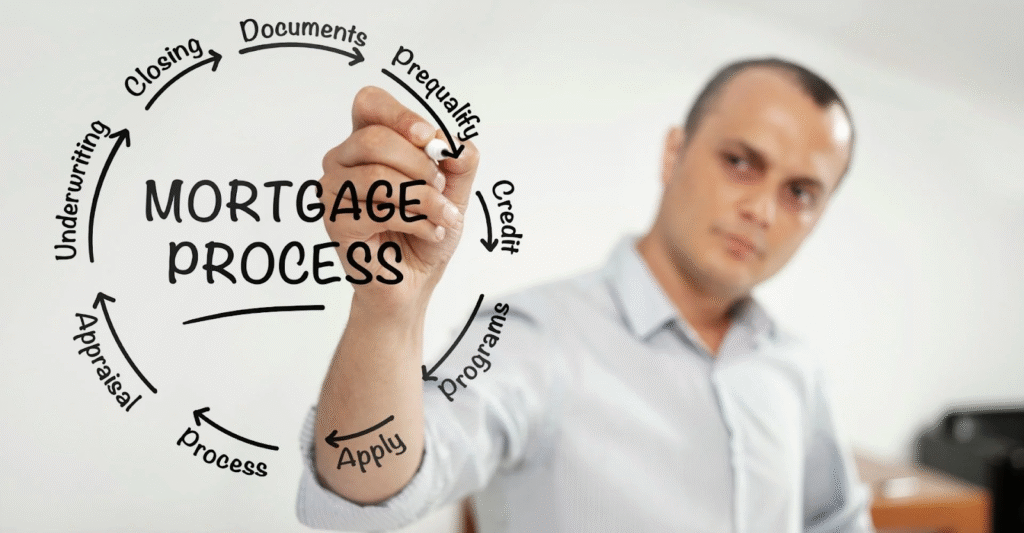

Step by Step Guide to the House Loan Process

Essential House Loan Documents You’ll Need